While latitude and longitude are universally recognized as essential components of astrological calculation, the role of altitude (elevation above sea level) remains poorly understood and frequently neglected in mainstream practice. This article examines the mathematical and astronomical foundations demonstrating why altitude constitutes a critical third coordinate in precision horoscope construction. Through technical analysis of horizon geometry, atmospheric refraction, and house system algorithms, I establish that altitude variations can produce measurable differences in house cusp positions exceeding 0.5 degrees at extreme elevations, a deviation with potentially significant interpretive implications.

Every natal chart requires precise geodetic coordinates: latitude (angular distance north/south of equator), longitude (angular distance east/west of prime meridian), and less recognized but equally important, altitude (vertical distance above the geoid). While celestial coordinates are calculated from the geocenter (Earth’s center), the astrological chart represents the sky as viewed from a specific location on Earth’s surface. This distinction between geocentric calculation and topocentric observation creates the necessity for altitude correction.

The traditional neglect of altitude stems from historical limitations: before electronic computation, manual calculations simplified by assuming sea level observation. Contemporary astrological software, however, operates without such constraints and can and should incorporate this third dimension for maximum accuracy.

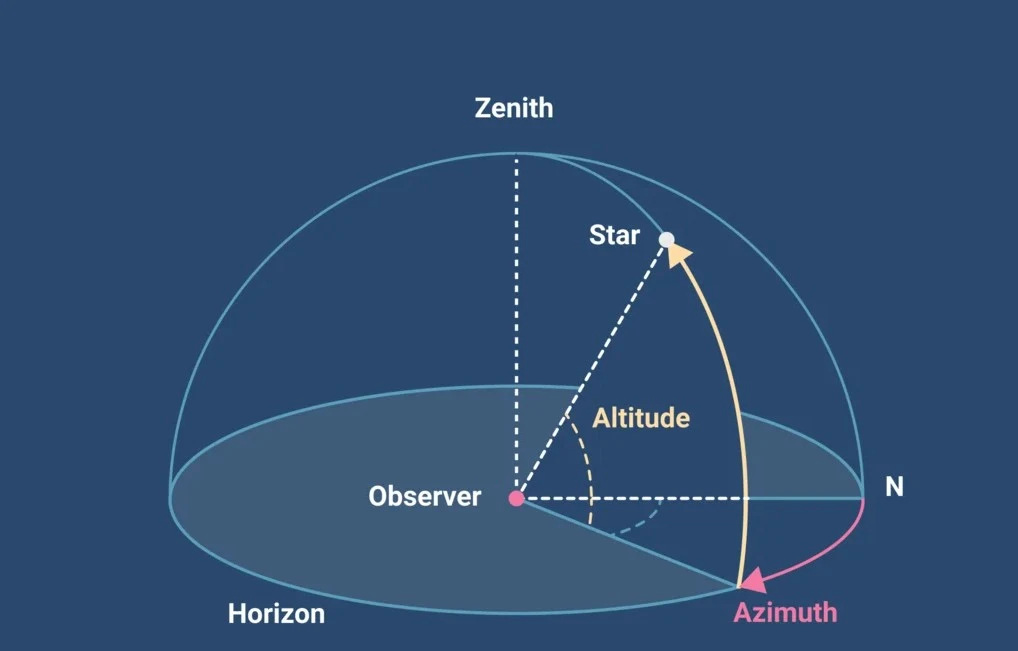

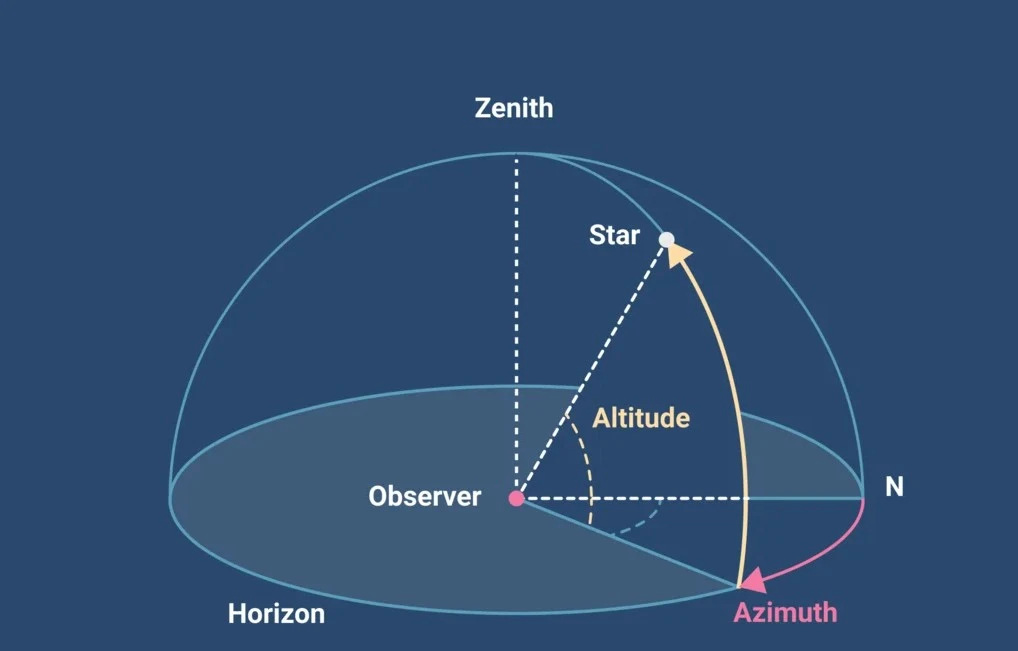

The fundamental plane of the horoscope is the local horizon, dividing the celestial sphere into visible (above horizon) and invisible (below horizon) hemispheres. The Ascendant represents the eastern intersection of the ecliptic with this horizon plane.

For an observer at sea level, the geometric horizon distance (d) can be approximated as:

d ≈ √(2 * R * h) where R is Earth's radius (6371 km) and h is observer height

However, this formula describes the horizon for an observer’s eye height (typically 1–2 meters). Altitude operates on a different scale entirely.

At significant altitude (a), the distance to the horizon extends substantially:

d = √((R + a)² - R²) = √(2Ra + a²)

For example:

This expanded horizon means the observer sees “deeper” into space, slightly altering the apparent angular relationship between celestial bodies and the horizon circle.

In house system calculations (particularly Placidus and related systems), the key parameter is the sine of the geographical latitude (φ). However, this simplification assumes observation from Earth’s surface. The corrected formula accounting for altitude is:

sin(φ') = (R/(R + a)) * sin(φ)

Where:

This correction becomes increasingly significant as altitude rises. For La Paz, Bolivia (φ = -16.5°, a = 3.64 km):

sin(φ') = (6371/(6371 + 3.64)) * sin(-16.5°) = 0.99943 * (-0.28402) = -0.28388 φ' = arcsin(-0.28388) = -16.497°

The difference of 0.003° (10.8 arcseconds) in effective latitude may seem trivial, but when compounded through house division algorithms, the effect on house cusps can be magnified.

The Topocentric House System, developed by Wendel Polich and Anthony Nelson Page in the 1960s, explicitly incorporates altitude into its calculations. The system’s name literally means “from the place,” emphasizing the observer’s specific location rather than an abstract geocentric position.

The algorithm calculates house cusps using the following relationship for intermediate cusps (2nd, 3rd, 5th, 6th, 8th, 9th, 11th, 12th):

tan(H) = (tan(RA) * cos(ε) - sin(ε) * tan(φ') * cos(OA)) / (cos(φ') * cos(OA))

Where:

The altitude enters through φ’, creating a systematic correction throughout the house calculation.

Even house systems not explicitly topocentric require altitude correction when properly implemented. The Placidus system’s fundamental trisection of diurnal arcs depends on the observer’s latitude. Using the uncorrected geographical latitude instead of the effective latitude introduces errors in:

The magnitude of this error varies with:

The following table illustrates approximate Ascendant shifts for various locations at 45° latitude, assuming birth time precise to the minute:

| Altitude | Location Example | Ascendant Shift | Equivalent Time Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 m | Sea level | 0.00° | 0 min |

| 500 m | Boulder, CO | 0.05° | 1.2 min |

| 1000 m | Denver, CO | 0.10° | 2.4 min |

| 2000 m | Mexico City | 0.20° | 4.8 min |

| 3000 m | Cusco, Peru | 0.30° | 7.2 min |

| 4000 m | La Rinconada, Peru | 0.40° | 9.6 min |

Note: These values are approximate and vary with latitude, with maximum effect around 45° latitude and reduced effect near equator and poles.

As light from celestial bodies enters Earth’s atmosphere, it bends toward the normal (vertical), making objects appear higher in the sky than their true geometric position. The standard refraction formula (approximately):

R = 1 / tan(h + 7.31/(h + 4.4))

Where R is refraction in arcminutes and h is apparent altitude in degrees.

At the horizon (h = 0°), refraction averages 34 arcminutes (over half a degree), accounting for the entire Sun/Moon disk appearing above the horizon when geometrically it’s still below.

Refraction depends on atmospheric density, which decreases with altitude. The approximate relationship:

R' = R * exp(-a/H)

Where:

For significant altitudes:

Primary directions, based on the key concept “one degree equals one year,” derive from the exact diurnal motion. Since altitude affects the precise Ascendant and Midheaven positions, it influences:

For a primary direction with an arc of 25.5°, an Ascendant error of 0.3° translates to approximately 3.5 months of timing error.

In local space charts and AstroCartoGraphy, the horizon plane becomes the fundamental reference. Altitude directly modifies:

A relocation to a high-altitude location without altitude correction produces inaccurate local space coordinates.

For precise eclipse timing and geographical mapping of eclipse paths, altitude affects:

Proper implementation requires:

The recommended calculation sequence:

1. Input: Latitude (φ), Longitude (λ), Altitude (a), DateTime (UT) 2. Correct latitude: φ' = arcsin((R/(R + a)) * sin(φ)) 3. Calculate sidereal time, nutation, aberration 4. Compute planetary positions (geocentric) 5. Apply parallax correction (especially for Moon) 6. Apply altitude-adjusted refraction for horizon contacts 7. Calculate houses using φ' instead of φ 8. Output: Chart with altitude-corrected angles and houses

Software should be validated against:

Consider a birth in La Paz, Bolivia (φ = -16.5°, λ = -68.15°, a = 3640m) on January 1, 2000, at 12:00 UT.

Without altitude correction:

With altitude correction:

While 4 arcminutes may seem negligible, it represents:

In a progressed chart 30 years later, this represents approximately 2 days of timing difference for solar arc directions.

Ancient and medieval astrologers observed from relatively low-altitude locations (Babylon: 34m, Alexandria: -2m, Athens: 70m). The significant altitude cities (Cusco, La Paz, Lhasa, Quito) were outside the classical astrological tradition. Thus, altitude correction remained undeveloped until modern computation made it feasible.

Today, with approximately 140 million people living above 2500m altitude (including major cities like Mexico City, Addis Ababa, and Denver), the technical need for altitude correction affects a substantial population.

Altitude constitutes a fundamental third coordinate in precise astrological calculation, affecting:

While the effects are generally small (typically 0.1–0.5°), they exceed the precision threshold of many astrological techniques and can shift significators across house cusps in marginal cases. Modern astrological software should incorporate altitude correction as standard practice, moving beyond the historical sea-level assumption to properly represent the three-dimensional nature of the observer’s position.

The integration of altitude represents the maturation of astrological technique from two-dimensional mapping to full three-dimensional spatial awareness, a necessary evolution for astrology’s continued relevance as a precision symbolic language.